The Running Game

I’ve written this blog in my head on many occasions in the past couple of weeks. Of course, now that I sit down to document all of those words that seemed to come so effortlessly at the time, they have retreated to a dark, cob-webbed, inhospitable corner of my brain, joining other subjects such as GCSE Science, how to iron a shirt effectively, and anything related to Plymouth Argyle success stories.

Anyway, for the previous two months now I’ve been running…quite a bit. The motivation for which came from multiple prompts, but in short it is down to a combined drive to lose weight, and to develop a healthier body and mind…..blah, blah, blah, etc, etc. Thus, in this blog post I’d like to share my insights on the mental torment, but ultimate joy that running brings, and the intricate battles that can leave you teetering on the edge of abject failure, or a warm sense of achievement. The reason I’ve written this post in my head so many times is due to the fact as I go round and round the park, lap after lap, I try to divert my thoughts towards anything but the run.

Now, I know what you are thinking – this new regime merely represents a temporary new year’s resolution-style commitment, which begins with an all guns blazing Mo Farah-esque dedication to pounding the pavement, and ends as quickly as it started with the disgraced sight of me sobbing into my Banks beer and whining about how I’ll never get fit!

However, so far after a few weeks of avoiding alcohol as much as possible (like Prince Harry avoiding the paparazzi at a costume party) and a dedicated program of running at least four times a week, I am currently beginning to reap the rewards, albeit slowly. I started modestly, managing just two laps of the nearby National Park here in Georgetown, and they weren’t easy laps. In the unrelenting Guyana climate it felt as if the heat was singeing my lungs and the ground gripping and clinging to my ankles. It is one mile from my house to the park, and each lap is also a mile in total. So, at that stage I was struggling to complete three miles.

Initially I began by running in the mornings at 5.45am, but that plan soon failed due to the fact I struggle to function without a cup of tea. I moved the runs to the early evenings and a couple of weeks ago, as the sun began to set over the park, and the guards prepared to lock the gates for the evening, I completed my seventh lap and mile eight of the run. Whilst taking great satisfaction in that moment, I think what pleased me more was the fact I didn’t collapse into a heap as soon as I exited the gate, but realised there was still some energy in the lungs.

I have run a little in the past, completing several half marathons, but I think this current period is the most consistently I’ve ever committed to it. Also, my previous running experiences took place in the UK, and running in the humidity and heat of Guyana presents a new challenge.

I’ve been reminded in recent weeks that the mental battle is far greater than the physical. So many factors unite to convince your brain that running is the most ludicrous idea in the world, and you are far better sitting in a chair, drinking tea, and reading a book. Conquering the urge to shut down and do nothing, as opposed to running has been a challenge at times.

During the working day my attitude to the impending post-work run fluctuates more erratically than Zimbabwean inflation. One moment I can’t wait to free myself from the computer screen, plug in the iPod and enjoy the early evening sun, and the next minute my legs feel like lead, and I convince myself I haven’t taken in enough fluids that day and if I run I’ll collapse in a heap and melt. I have found though that there are two main factors which have helped me edge the battle so far;

1. The Running Playlist

In recent weeks I have been reminded of the magnitude of the perfect running playlist. The monotony of each lap would be too much without music. Getting your playlist right can propel you, but getting it ever so slightly wrong is a jogging calamity. I haven’t yet quite perfected it. I’m often close, but there are always one or two rogue tunes that simply don’t work on a running playlist and thus completely upset the applecart (the applecart carrying my mental strength).

Presently one particular song causes a confusing mix of humour, suppressed rage, minor insanity, strained vigour, and sporadic muscle spasms (but not necessarily in that order). It’s also a song that proved to me once and for all that I’m a little odd. I’ll verify this (not that I need to I hear you cry) by revealing here and now that about fifteen minutes into my running playlist comes ‘Zorba the Greek’ performed by the ‘Flying Dutchman’ – Andre Rieu. That’s right, quite possibly the worst song that could ever appear on a running playlist, it’s ridiculous. The song is wonderful of course…if you’re sat in a little Greek taverna supping red wine and eating moussaka. However, when you’re desperately attempting to establish some flow and rhythm in the early stages of a run it’s a complete nightmare! The fact is though I can’t delete it; because you see, what I have noticed is despite it completely ruining my stride and breathing, it makes me smile, pure and simple. At a make or break point when I’m usually on the cusp of succumbing to the heat and a complete lack of willpower, it pushes me on by actually making me take the run a little less seriously and diverting my thoughts away from the struggle.

Other songs interspersed on my running playlist, which also perform this task (but also confirm my weirdness) include ‘Ra Ra Rasputin’ by Boney M, ‘Come on Eileen’ by Dexys Midnight Runners, ‘What is Love’ by Haddaway, ‘Delilah’ by Tom Jones, and ‘Surfin’ USA’ by the Beach Boys. I should be chronically embarrassed by all this, but sometimes I think you get to a point in your life when it’s too late for that…especially when the whiteness of my legs is a far more obvious and immediate embarrassment when running in the park here. I’m officially the man who cannot tan.

2. Fellow Runners

I hadn’t realised how important it is to have fellow pavement pounders around me when I run. There was a day a few weeks back here in Georgetown when the heavens opened and the wind whipped in over the seawall into the park. I decided to run anyway given that it at last seemed the perfect temperature for exercise. Upon arrival I found the park to be empty, not a single soul visible. I scoffed a little at the fair-weather attitude of the other park-goers and felt a little smug that I was there, laughing in the face of the wind and rain. Two laps in and the laughter had gone, the smugness had slinked away through the gate, and I was struggling severely with motivation. I soon realised that it was because I was not surrounded by other runners. I had no inspiration, no one to compete against, and essentially no one to drive me on. Not even Zorba the Greek or Boney M could propel me this time.

I struggled through the run and that evening I thought about just why it had been such a battle in the empty park. It may sound ridiculous, but I concluded that in the previous weeks I had gained a very certain familiarity with not just the park, but even more crucially its regular visitors. Running lap after lap is a monotonous and sterile exercise. However, the faces you pass make it interesting. They become familiar, and thus, reassuring. You begin to reason that surely if other people are doing this it must be logical.

Then there’s the facial expressions and gestures which become commonplace. There are several fellow runners who over the course of the past few weeks have developed from complete strangers to several different stages of relationship (in this order),

1. Glancers

2. Timid grinners

3. Broad smilers

4. Timid grin head nodders

5. Broad smile head nodders

6. Broad smile, head nod and eye rollers (in a manner which evokes the emotion ‘here we are again!’)

7. Tennis invites (the other day a man invited me to play tennis with him!)

During one run I was stopped mid lap and asked if I wanted to join a group of people for a beer and some freshly baked fish, and another day I was stopped by a very friendly and interesting American chap who completely ruined my run, but had some great tales about his life in Africa. I’ve even on a couple of occasions seen fellow runners outside of the park going about their normal lives, and we’ve struck up conversation. It always begins with confused looks at each other and then it clicks – we know each other from the park. I had wondered if one day I’d meet my future wife during one of my runs, but soon reminded of the whiteness of my legs, I let this ambition fade!

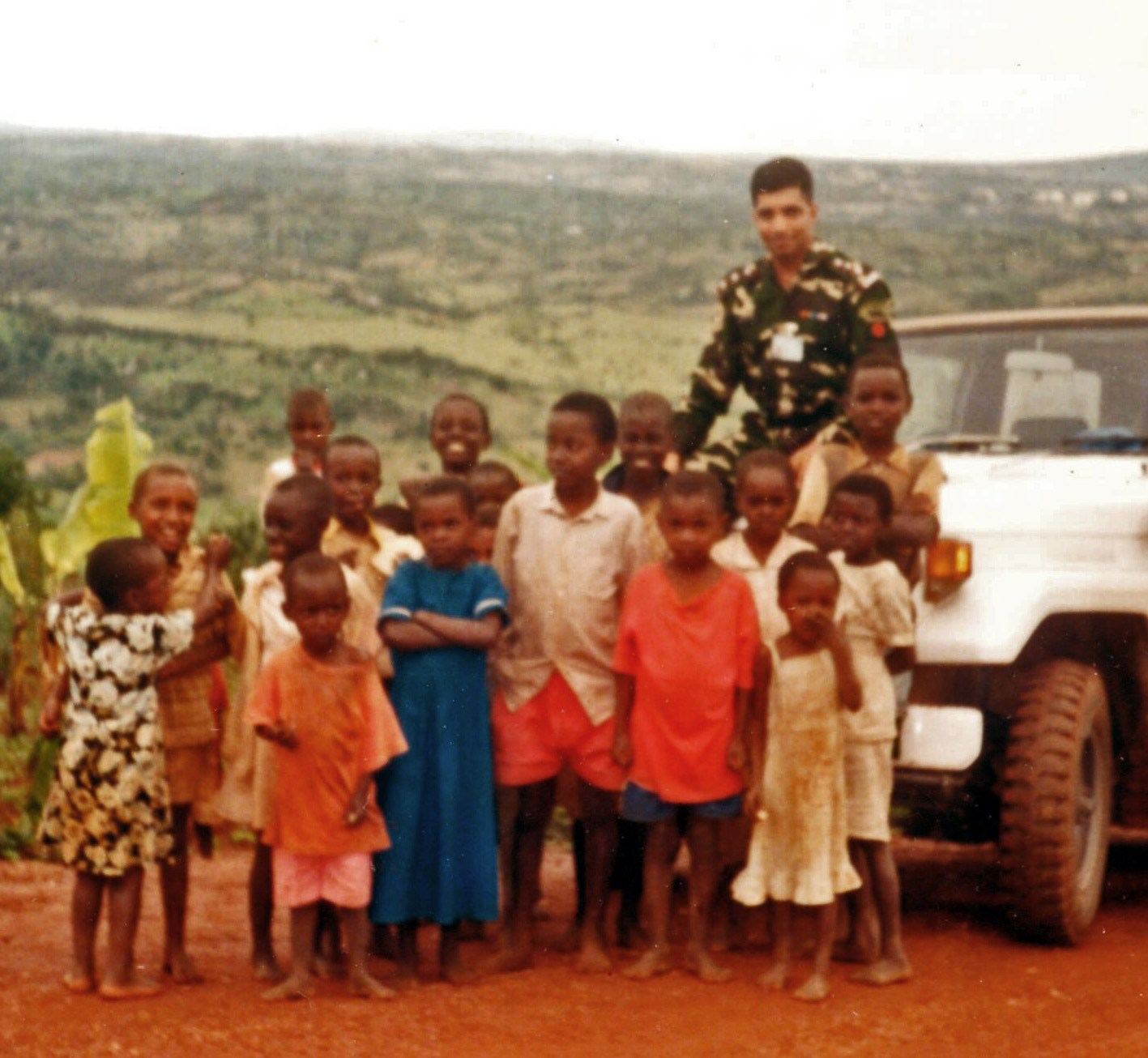

Despite running very regularly for almost 3 months now, it still presents an up and down journey of mental torment. Some days the run flows by in a breeze, other days I vow never to go again. One day I don’t think I ate enough and literally thought I was going mad as I felt light-headed and almost as if I wasn’t quite there mentally! However, on most occasions now I am able to transform the endless monotony of the continuous laps into an almost peaceful content monotony. It does also help a great deal that the park is a picturesque location, as hopefully the accompanying photos testify.

I always walk home from the park to warm down and it’s at these moments I feel at my most positive at any point during the day, which does prove (to me at least) that exercise can have such a decisive effect on your mental wellbeing.

The title of this blog post is a song by Kula Shaker, which incidentally is not on my playlist, but I feel it sums up my relationship with running perfectly.